AT the end of February, when Studio Daniel Libeskind was named winner of the design study on the future of the World Trade Center site, it was only the latest sign of the degree to which celebrity has come to dominate high-profile architectural practice. Mr. Libeskind prepared his scheme with the help of a 27-member architectural staff, not to mention engineers, photographers, landscape designers and a ''slurry wall consultant.'' To judge from the way he and the press have treated his design, though, he might as well have created it by himself, working in the sort of cloistered isolation we associate with painters and novelists.

But famous architects and their publicists may not want to celebrate yet. It turns out that while the solo-star model won the ground zero battle, it may be losing the war. The list of finalists named in December also included several teams who joined forces for the occasion, including Think, led by the New York architects Rafael Viñoly and Frederic Schwartz, which survived along with Mr. Libeskind to the final round.

That model attracted criticism during the Modernist movement and again in the 1960's as a counterculture ethos seeped into architecture. The critique continued among a small group of architects who came of age in the 1970's -- including the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, who made collaboration with other architects a rhetorical priority early in his career -- and among husband-and-wife partnerships, like Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown or Ricardo Scofidio and Elizabeth Diller.

An earlier generation of collaborative firms, like the famous London-based Archigram, whose collapse began perhaps not coincidentally as it began to land actual commissions in the late 1960's, were essentially, and sometimes vehemently, anticommercial. The new collaboratives are filled with ''hard-core entrepreneurs,'' said Christopher Hoxie, 34, who works at KD Lab, a New York firm whose Web site says its members are ''intent on exploring the blurred boundaries between architecture, graphics and film.''

''When we formed in 1999 there weren't many firms like ours,'' said David Erdman, 32, a partner in a firm called Servo, whose four founders met while studying architecture at Columbia. ''Now they seem to be all over the place.'' In fact, the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Triennial that opened this week in New York features the work of a Detroit collective called Co-lab as well as the New York firm Collaborative.

Some of the young firms, like the New York-based SHoP/Sharples Holden Pasquarelli, have stuck to pledges to avoid using unpaid interns, remembering their own anonymous toil at firms with famous principals. And in a nod to Mr. Koolhaas, who calls his Rotterdam firm Office for Metropolitan Architecture, there is now an alphabet soup of young firms with intentionally anonymous or bureaucratic-sounding names, from Architecture Research Office to Foreign Office Architects.

Mr. Koolhaas, in fact, stands as a one-man symbol of a profession torn between lone and collective models of practice. He often speaks of himself as an avatar of a shift toward cooperation. ''If I pride myself on one thing, it is a talent to collaborate,'' Mr. Koolhas told The New York Times in 2001.

On the other hand, Mr. Koolhaas remains without a doubt one of architecture's brightest individual stars, with name recognition exceeded perhaps only by Frank Gehry and a handful of others. And his recent efforts at collaboration haven't been particularly successful; plans for a hotel on Astor Place in Manhattan, conceived with the Swiss firm Herzog & de Meuron for the design maven and hotelier Ian Schrager, fizzled out last year. Mr. Kennon said: ''Rem talks a lot about collaboration, but at the end of the day he isn't that interested in actually doing it himself.''

He is not the only one. The process of collaborative architecture raises potential problems among clients and architects alike. Some clients demand a signature design that reflects an individual inspiration, or simply prefer working with a single contact. Others worry that too many cooks will spoil -- or water down -- the proverbial broth.

''Some clients think that's what genius is -- the lone visionary,'' said Richard Fernau, who runs a firm with Laura Hartman in Berkeley, Calif. ''But compromise is fundamental to the profession.''

Others, though, doubt whether a fully collective design process can ever produce a great building. Mr. Riley of the Museum of Modern Art said: ''Ego is very important in architecture. Imagine a movie without a strong director, with all that goes into it. If the sound person, the lighting person, the cinematographer, if they all had an equal voice, imagine how awful it would be.''

The new collectives have taken a variety of forms. While some designers favor an incubator model, with several firms, under one roof, collaborating on an occasional basis, others have set up networks of one- or two-person offices in several different cities. E-mail, mobile phones and Internet-based design tools make the dispersal possible. Servo, for example, has micro-offices in Los Angeles, New York, Stockholm and Zurich. ''Instead of single authorship and branded identity, we're trying to develop multiple authorship and flexible identity,'' said Servo's Mr. Erdman.

The experiments in collaboration at ground zero reflected a recent movement in the field away from solo practice and in the direction of collective endeavor. Among architects in their 20's and 30's ''there has been a nearly permanent shift toward various kinds of collaborative practice,'' said Terence Riley, curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art and a member of the panel that considered more than 400 ground zero entries.

These days, young architects are forming collaborative firms right out of architecture school; many don't even consider jobs with traditional firms, where they worry they will have to spend years designing bathrooms and closets.

''Part of the collaborative spirit among younger architects is that they're seeing what's required to compete in a profession dominated by fame and by track record,'' said David Rockwell, who worked with the Think team. In an effort to gain notice, he said, young architects -- emboldened because they can first support themselves with computer-based design work -- are banding together.

Mr. Riley added that the ground zero teams, rather than setting the stage for a new model of practice, instead offered evidence that an existing trend among younger designers was ''trickling up'' to the field's more established figures.

One of those ad hoc teams, a collection of six midsize, computer-savvy firms called United Architects, has decided to keep its group intact. Greg Lynn, one of the team's founders, said that the United members will maintain their individual firms but work together on selected projects and keep open a group office, staffed by two full-time employees. United has already been shortlisted in a competition for a commercial complex in Frankfurt.

''The real discovery of this whole World Trade Center process, even more than our scheme, has been United Architects itself,'' said Kevin Kennon, a member who runs his own practice in New York.

A tension between individual vision and teamwork has long been palpable in architecture. And for every Frank Lloyd Wright or Norman Foster, there have always been countless firms run as equal partnerships. But ''for a certain generation -- Richard Meier's generation, say -- their idea of architectural practice was centered around the idea of the sole practitioner,'' Mr. Riley said. ''A number of them had partners, but there was always a clear distinction made that one was the designer and the other partners worked on other issues'' -- that they were partners in a business sense but not a creative one. ''The inference was that the way architecture is best made is when an individual is confronted with an architectural problem and comes up with an individual solution.''

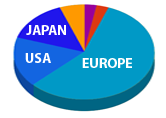

Indeed, most of the best-known architects in this country and in Europe have spent the bulk of their careers alone at the top of a firm's pyramid. They have carefully cultivated themselves as one-man (and occasionally one-woman) brands. Mr. Viñoly, no slouch in the brand-name department himself, described the ruling approach as having developed out of ''this 19th-century notion that a building comes from one man's head.''

ivi Sotamaa, 31, a partner in Ocean North, which has small offices in Helsinki, London and Oslo, said, ''We founded our firm as a sort of test, to see whether you could use new technologies to practice architecture in a new way.'' The firm is at work on projects ranging from ceramics and furniture design to urban planning; its partners, who include Mr. Sotamaa's sister Tuuli, 28, earn revenue from teaching, grants and consulting as well as architectural commissions.

Mr. Sotamaa said Ocean North's partners were eager to avoid a ''traditional architectural process, where one person has a vision and sketches it out and then everybody else works toward that vision under his guidance. I wouldn't call our setup anti-hierarchical, exactly. But the hierarchies shift from project to project.''

Young as he is, Mr. Sotamaa is already a veteran of the new approach, having helped found an earlier, slightly larger version of the collective in 1995, when was 23. That may explain the somewhat jaded way he talks about the firm's history. ''At first we had a totally idealistic sense of collaboration,'' he said. ''But we've learned the hard way what you can and can't do with new technology. We make extensive use of the Web and all its design possibilities, and we keep the design process open and flexible in the early stages.'' Usually, he said, a single partner will take charge of a design as it nears completion. Mr. Erdman said Servo worked much the same way.

Mr. Sotamaa, for his part, doesn't shed that world-weary tone when it comes to discussing the World Trade Center collaborations, especially those, like the Dream Team composed of Richard Meier, Charles Gwathmey, Peter Eisenman and Steven Holl, that were made up of architects who had rarely worked with other strong-willed peers. It is a tone that seems to reverse the natural order of things -- the tone of a fresh-faced veteran giving advice to a rookie in his 70's. ''I was skeptical at first that architects of that stature and that generation could collaborate,'' he said. ''If you haven't worked that way before, it can be difficult. It's taken us a lot of time, a lot of trial and error.''

Still, he said, with only a trace of condescension, ''the bottom line is that I thought it was fantastic that they were willing to give it a try.''

From The New York Times; originally title Goodbye 'Fountainhead,' Hello Kibbutz By CHRISTOPHER HAWTHORNE April 27, 2003

0 comments:

Post a Comment